During the third week of our 10-week research program with student researchers from Swarthmore, students interviewed experts and local community partners about what citizens could do to support pollinator habitat and populations in the city. This is an issue vital to POP, as nearly all of our fruit crops are dependent on insect allies like bees, butterflies, wasps, and moths for successful pollination and fruit production. For this reason, all POP orchards include pollinator gardens, often interplanted in the orchards’ understory.

Momi Jeschke interviewed Tom Sullivan of Pollinators Welcome, a gardener, landscape designer, workshop leader, former honey beekeeper and public speaker, who’s been working since 2009 on native bee conservation. Special thanks to GrowAbility partner Ethan Brazell of Elwyn Davidson School who put us in touch with Tom, his uncle, as an outgrowth of our work providing special needs-adapted curriculum on native and honeybees as part of our ecological stewardship program for special needs students.

In the Q&A below, Tom shares some incredible advice about becoming a steward of pollinator habitat through planting diverse landscapes with multi-season bloom periods and also creating opportunities for communities to connect through seeding habitat, as with the seedball project he helped organize with 9th graders and members of the indigenous community of Massachusetts.

Jeschke: In your experience, in what ways do the native populations differ from the non-native bees you’ve studied in terms of habitat requirements, threats to their populations, diets, and plant-preferences, and how can people of native Pennsylvania help accommodate these differences?

○ Tom: There is not too much difference between native populations, “native” signifies that they are native relative to the area. Species differences differ geographically, and most of that contributes to the climate and habitat of their respective locations. For example, most species located in the southwest/southern California don’t need to deal with moisture so much, so that is one difference that is based on location. Most species are ground dwellers, and make their nests in the soil. The exception is honeybees, who generally make their nests above ground. 30% of native species live in wooden structures, hollows in trees, etc. There are about 4,000 species of bees in the continental U.S., about 400 species in New England, and more than 400 in Pennsylvania. The most important thing to remember when attempting to accommodate differences between native and non-native species, is that native species are generally more attracted to native plants. Planting native plants is one of the best things you can do to create a habitat for bees. Other things you can be aware of is nurseries in PA who supply native plants, a really good one is North Creek Nurseries in Landenberg, PA. When designing habitats, create for the masses, not specific species, the more bees of different types you can attract the better. Focus on a 3-5 foot swath of flowers, that is the ideal height for bees. In addition, mix up your flower families, the more you mix the more species you will attract!

Jeschke: In your article in the Gazette about bee and pollinator importance, you mention the necessity for bees to have suitable habitat, the proper plants and trees necessary for them to attract the bees. For an urban place like Philadelphia (or for people with limited space), what plants would you suggest people grow in order to attract bees and create

more of a safe space for these bees?

○ Tom: Some general advice for people just starting out with gardens, particularly with limited space, don’t plant sprawling plants if you don’t have a lot of space, compact plants are better. Also bear in mind bloom calendars. It is important to have at least three blooming plants per season (spring, summer, fall) so nine plants total. You can find many of these plants at your local nursery. Check out this plant list Tom shared, 25 Native Plants that Attract 7 or more Native Bee Genera.

(In an earlier conversation with Alyssa about other methods for creating habitat involving youth and suitable for all-ages , Tom shared about his work with planting native and wildflower seed balls, which became a big inspiration for our group’s later work to create and distribute seed balls with students for schools and during POP tabling events).

Jeschke: Can you tell me a bit more about the seed ball project that you on with students and indigenous community members in Massachusetts?

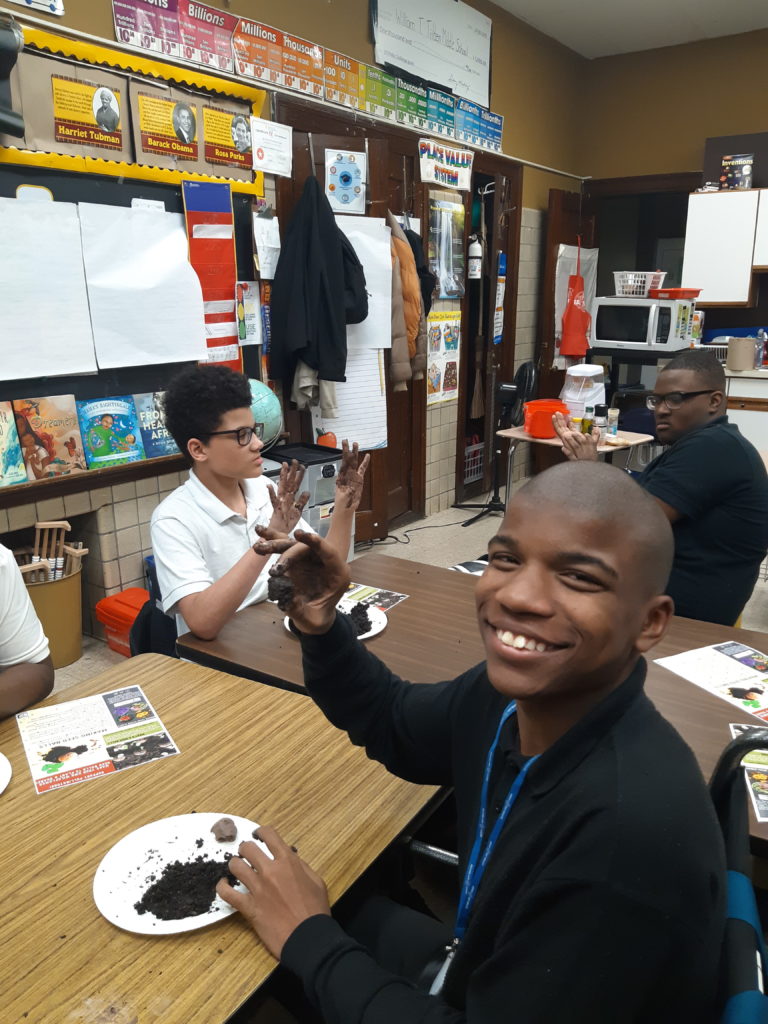

○ Tom: So the actual seed balls we made out of clay, compost, and a little bit of water, basically we wanted it to be moisture holding (like peat moss). So a charter ninth grade school, we made 982 seed balls in three hours with 38

students. The event was organized by the science teacher and we had two

Native American organizations join us. We were set up in the auditorium; first we mixed the clay, then we made the balls, then cleaned up the space. We had a storyteller by the name of Brule from one of the Native American organizations, tell us stories while we opened up the balls and dabbed the seeds into the center, and rolled the balls back up. It was a very magical experience, and I received letters back from the students saying how much they appreciated the experience which really touched my heart. The next step was to take the seedballs to a Native American site Wissatinnewag, we went on two occasions, and the second time the Chief Bigtoe joined. We were instructed to leave minimal changes to the land; the land is an ancient burial site, Wissatinnewag, located in Greenfield, MA above the Great Falls. The site was a holy spot in which tribes collected in peace and caught fish. The seed balls were placed in the tracks left by coyotes and deer, and lightly touched the balls in. The event ended with Chief Bigtoe performing a ceremonial burning with a large eagle feather. It was an amazing

experience and I was very thankful to have been a part of it.

Jeschke: What have you observed in landscapes you’ve created that show you that the habitats are being restored for a variety of species?

○ Tom: Well the best thing you can do is to observe them coming to the

flowers, you know then they are getting fed. Increased observance of bees is the best sign, since it is very hard to find out where they are nesting. If you want to know where they are nesting, create nesting grounds. There are two different ways bees approach a flower, since they need protein, which can be found in the pollen, and carbohydrates, which can be found in the nectar. If the bees are searching on top of the plant, they are looking for pollen, if they are nose down in the plant, they are usually looking for nectar.

Jeschke: What are some ways everyday people can be better advocates for our threatened pollinators?

○ Tom: The most important thing you can do to be a better advocate for bees is to raise awareness about the problem! Getting the word out is so very important. The problem is still getting worse, not any better. Another thing you can do is to realize that bees are native and are very good pollinators, and that you should feed them and make them safe. You can do a lot by planting. MAKE SURE the your soil and the soil you purchase does not have toxins!! In particular, neonicotinoids. While neonicotinoids are synthesized, they are present in nearly everything. Since the introduction of neonicotinoids, which were first introduced in the ’90’s, bee populations have severely declined. Neonicotinoids can live in soil for up to three years. The toxins in the soil are transferred to the plants, and any insect that eats the plant, including the nectar/pollen of that plant, will die. The

state of Maryland became a neonicotinoid free-state. One of the best things you can do is buy neonicotinoid-free plants and soil. Something Philadelphia Orchard Project can do is list the neonicotinoid-free plant nurseries.

This POP Blog Post prepared by Swarthmore student researcher Momi Jeschke with support from POP Education Director Alyssa Schimmel.

SUPPORT US! If you found this entry useful, informative, or inspiring, please consider a donation of any size to help POP in planting and supporting community orchards in Philadelphia: phillyorchards.org/donate.