POP Orchard Director Alkebu-Lan and I were weeding the food forest orchard at the Fairmount Park Horticultural Center on a humid late July afternoon, when I saw a dragonfly unlike any other that I had seen before. In between breaks from sudden, summer cloud bursts, it zipped quickly through the air, landing on a branch in among the asters, long enough for us to observe it. Its bright turquoise face, black-and-white zebra-striped body, and shimmering light blue tail captivated me, catching my curiosity in questions about its life and interrelationships in our local ecology in these times of intensifying climate change.

I was able to get a photo of it, and with Google image search, I came to learn about the Blue dasher (Pachydiplax longipennis), the only member of the Skimmer family Libellulidae, the largest and showiest dragonfly family. According to the University of Wisconsin Milwaukee College of Letters & Science, its range stretches across North America from British Columbia to Ontario, south (except for the Rockies and Dakotas) to California and Florida, and reaches into Mexico, the Bahamas, and Belize. According to dragon-fly citizen-science tracking project Wisconsin Odonata Survey, Blue dashers have been observed to have been extending their range further north in recent years.

Given its wide range and ubiquitous presence, the Blue dasher is one of the most studied of dragonfly species and are known for their habit of perching on warm days to minimize the angle of the sun’s rays, by drawing their wings forward and raising their bellies vertically (like a pencil on its point). We observed this behavior when it landed, when we were also looking for ways to cool off from the sun’s heat! Usually living near ponds, ditches, and marshes, it’s said that they also tolerate low-oxygen or poor quality water, often being cited as biological indicators for water quality. These excerpts on some of their behaviors and characteristics are just touchpoints in the larger learning on this species, its behavior, and one tiny thread in the web of relationships in which it exists.

I share this brief anecdote to uplift the potential of orchard spaces, and any natural space — sidewalk green space, open lot, corner market container planter — as spaces of important ecological observation that can harness curiosity into question and research, pattern mapping, hypothesis, and broader, natural systems-based learning. In uncertain times, taking time to observe the natural world can help us locate ourselves in place, help us to understand the relationships among species, and fuel conversations around conservation.

Regular nature observation is the primary practice and basis of citizen-science, a field that’s growing ever more popular with use of websites and phone apps like iNaturalist that allow users to aggregate their individual observations by snapping photos of plants, animals, fungi, and insects to identify these species and map them geographically among other user-submitted data. This information can help to highlight species’ presence in a particular place, track migration patterns or movement of species, and note factors related to their health and survival into future generations. These digital tools provide a powerful opportunity for citizens to be engaged with the natural world as scientists and advocates for conservation. The possibilities for engaging citizens in regular observation of their local ecologies is promising!

In a 2012 article ‘Observation of everyday biodiversity: a new perspective for conservation?’ published in Ecology & Society journal, authors Consquer, Raymond, and Prevot-Julliard found that public involvement is one of the keys to achieving biodiversity conservation goals, making people more aware of nature in an ordinary and local context and its value in their everyday lives. They found that repeated interactions with nature influenced the development of people’s knowledge of biodiversity’s importance, leading to the formation of their own pro-conservation attitudes and increased likelihood for aligned & changed behavior at the individual level.

As teachers, families, and students prepare for the upcoming school year, whether in a classroom, attending virtually, or using the city’s natural landscapes as an outdoor classroom, I propose that we engage students of all ages in participating in regular nature observation and data mapping in the orchards and beyond.

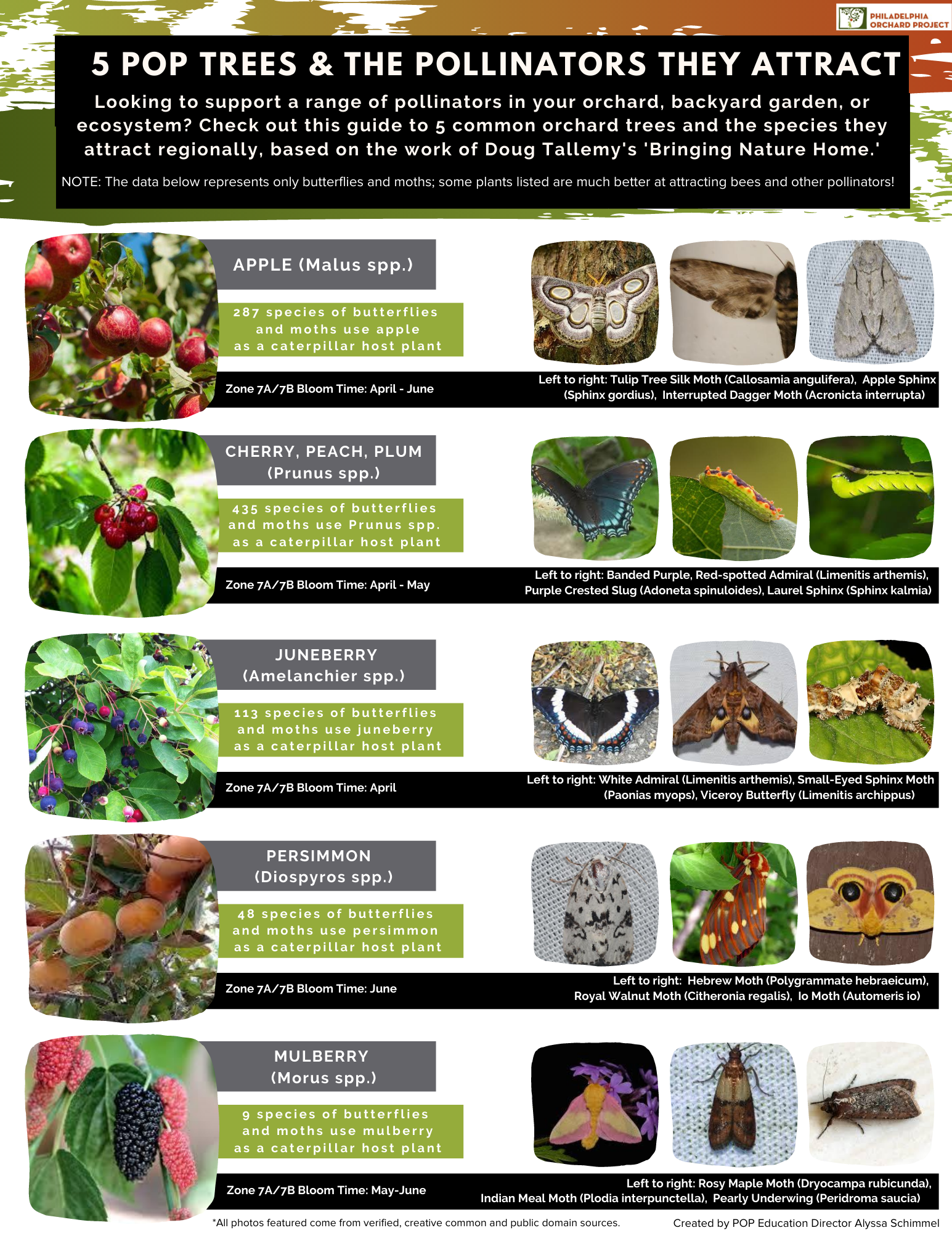

To that aim, we offer this set of lesson materials that for use with upper elementary through high school students — including a slideshow, info sheets on common plants of the orchard (trees, shrubs/vines, herbs) and the moth and butterfly species they attract, along with data tracking sheets. These materials were created in partnership with the Swarthmore student researchers who teamed up with me last spring: Bethany Bronkema, Aaron Urdiquez, Momi Jeschke, and Daria Syskine.

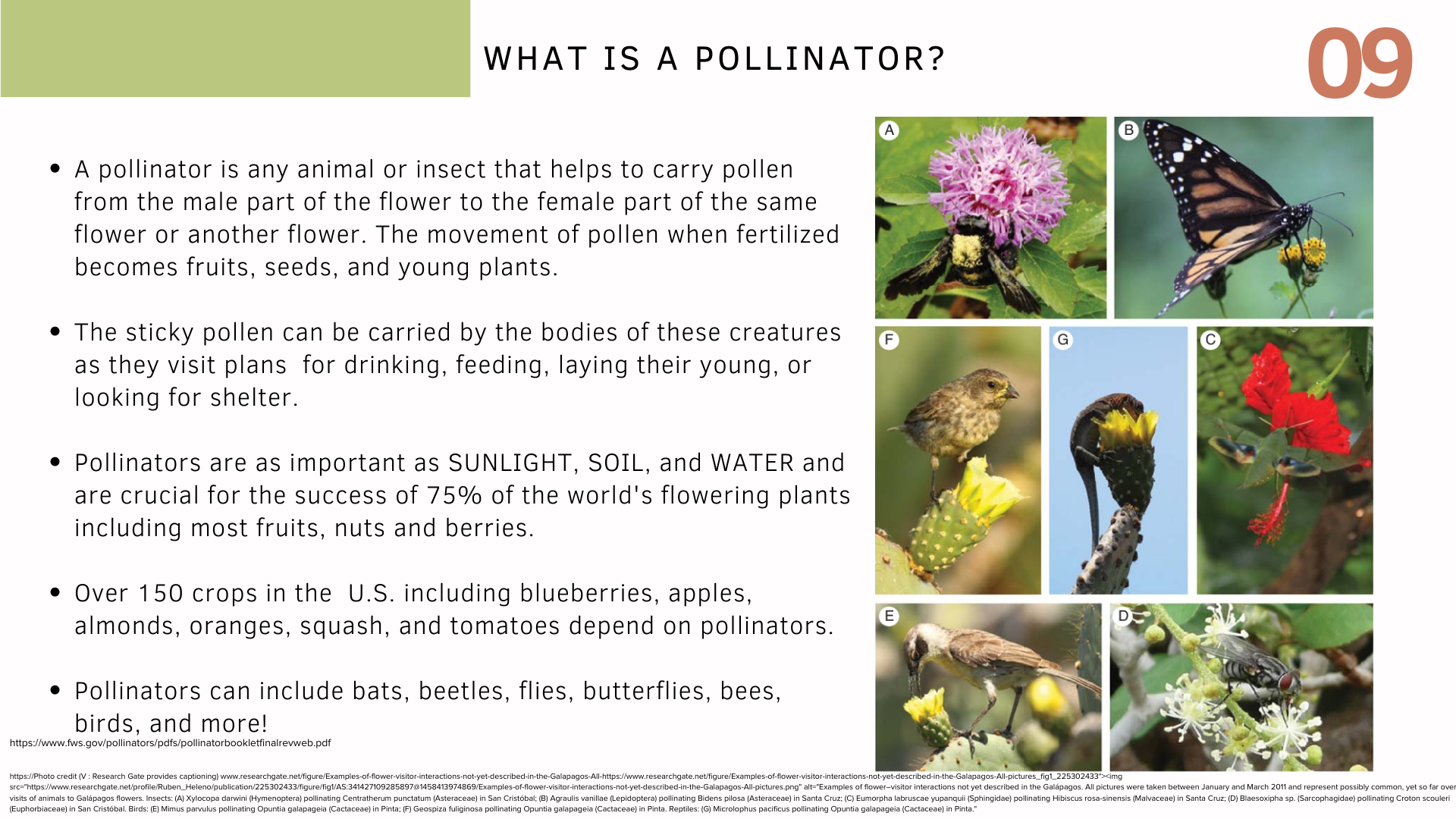

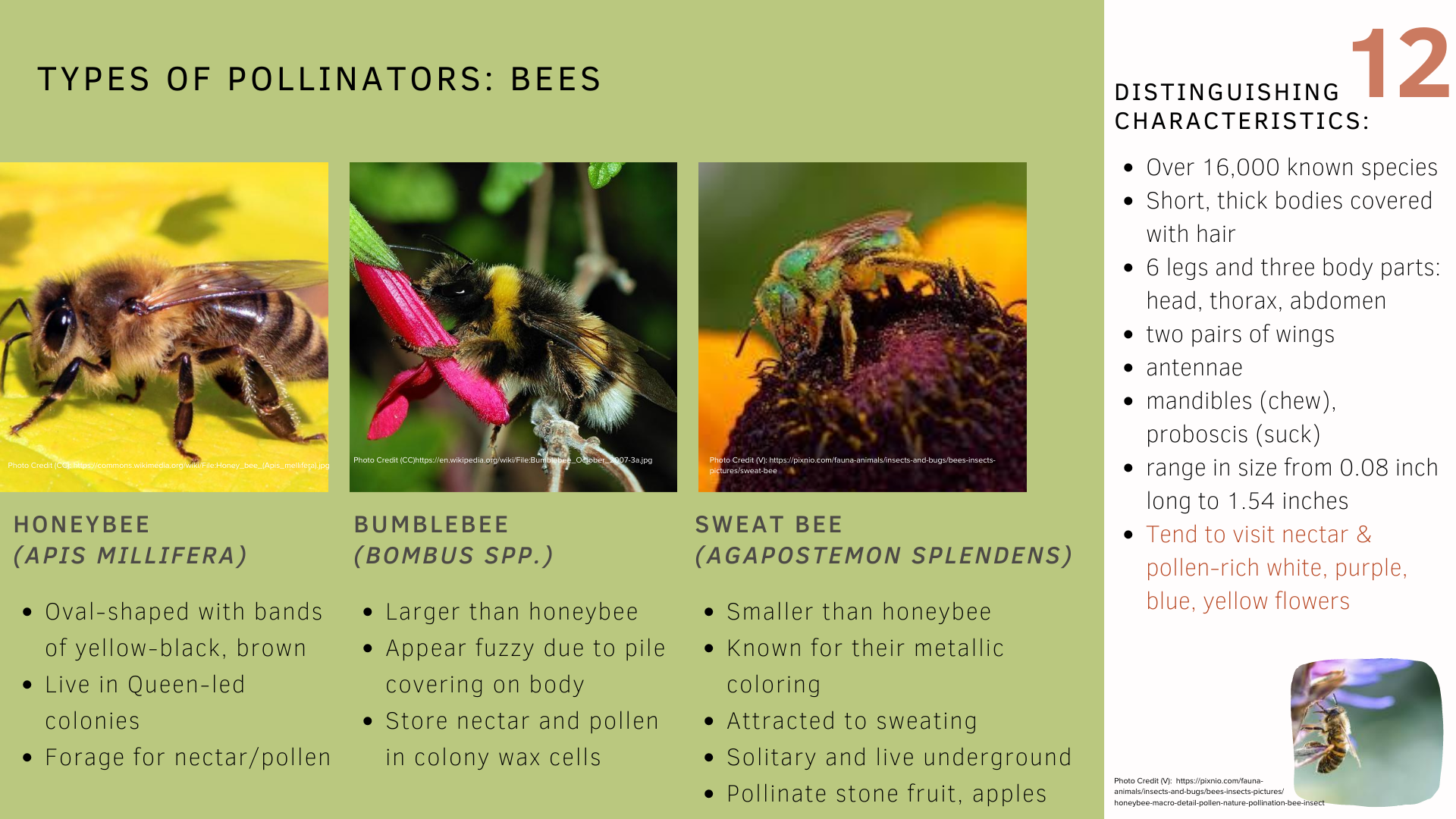

While the info sheets are focused mostly on butterfly and moth species due to finding the most aggregated information on these species through Doug Tallemy’s Bringing Nature Home database, teachers might adapt this frame for focusing on a variety of other pollinator species such as dragonflies, birds, and bees. Other possible adaptations or extensions with this set of materials include encouraging students to do deep dive research on the particular species they identify in the orchards, creating art, poetry, songs, or videos from it. Older students could undertake research on current conservation efforts on the habitat of the identified species, or engage in advocacy work such as create an issue brief, or sending letters to elected officials at state, local or federal levels on actions they can take or legislation to pass for environmental protections.

For an entertaining and informative look at principles of ecology that can help guide students in framing of future scientific inquiry, consider checking out Crash Course’s Hank on Ecosystem Ecology video playlist along with the following citizen-science apps and websites for observing of your local ecology! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v6ubvEJ3KGM

iNaturalist https://www.inaturalist.org/

Nature Serve https://explorer.natureserve.org/AboutTheData

Insight Citizen Science https://insightcitizenscience.com/

Odonata Central (dragon-fly specific) https://www.odonatacentral.org/#/

Bumble Bee Watch (bumblebees) https://www.bumblebeewatch.org/

Monarch Milkweed Mapper (monarch butterflies) https://www.monarchmilkweedmapper.org/

Happy observing! Let us know how you use and expand upon these materials with your students!

This POP Blog Post and lesson materials were written by POP Education Director Alyssa Schimmel.

SUPPORT US! If you found this entry useful, informative, or inspiring, please consider a donation of any size to help POP in planting and supporting community orchards in Philadelphia: phillyorchards.org/donate. POP’s School Orchard Program is funded in part by the Rosenlund Family Foundation, the Dolfinger-McMahon Foundation, and the Isenberg Family Fund.