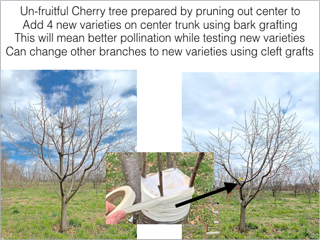

A small group of established pear and cherry trees at Philadelphia’s Saul High School orchard had never fruited well. What to do? Replanting costs time and money. What practices might address this situation while at the same time growing both gardens and gardeners?

In March 2020, Phil Forsyth of the Philadelphia Orchard Project (POP) asked if I would demonstrate a rarely practiced form of grafting done on established trees known as topworking, which uses various techniques, including the cleft graft and bark graft.

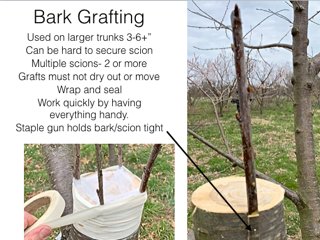

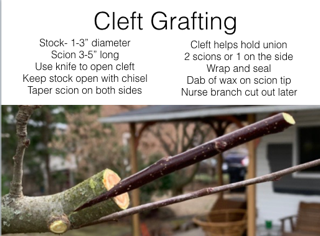

Topworking uses less common techniques than the more familiar whip and tongue graft and others that typically match up small similar sized pieces. Cleft and bark grafting techniques match up the larger limbs of an existing tree with smaller scion pieces of a new variety of the same species, which will grow on top of an existing fruit tree, adding branches of new varieties.

So, rather than planting a new tree from the ground up, you are ‘rooting a cutting’ not in the soil, but in the cambium of an existing tree. Each bud that grows from this union will be as if a new tree had been planted—not at ground level but in the canopy of a compatible tree. This method is called topworking.

If anything could be called tree-surgery, it’s topworking. And like surgery, it’s not for the faint of heart; yet once you’ve experienced what it can do, it will take your gardening skills to another level.

Check out Mason’s short video on the lost art of topworking:

Like and share if you found it helpful!

When we graft, we join hands, as it were, with gardeners who came before us and who passed these cultivars along to us. We become part of this continuing story by perpetuating their presence in our gardens and passing these varieties along to future generations to enjoy. For me, this kind of activity is what puts culture into the heart of agriculture and horticulture.

Every plant variety has a story that connects it to the lives of people, plants, places, and various struggles.

Think I’m exaggerating? Consider the Peace Rose.

Before Marco Polo, Europe only knew red, pink, and white roses that bloomed once a year in May. The rose Marco Polo brought back from China was yellow and bloomed repeatedly. Thus the hybrid rose breeding craze began. Just before Paris fell to Nazi occupation, scion sticks of a new, un-named rose were put on the last plane to leave the city. Later, blooms were distributed among participants at the first meeting of the United Nations in San Francisco and given the name ‘Peace’ in hopes of a new era. Plants are our companions that have helped make Earth habitable. It is natural that we honor them as part of our ancestral story along with all our other precious heirloom plants and animals.

Vollmer completing cherry bark grafting; successful bark grafts budding out; and a successful cleft graft.

This blog article written by Mason Vollmer, horticultural educator and author. Check out his writings, including books on school gardens and community nurseries at http://www.thesocialgardener.net/

SUPPORT US! If you found this entry useful, informative, or inspiring, please consider a donation of any size to help POP in planting and supporting community orchards in Philadelphia: phillyorchards.org/donate.