Murta fruit look somewhat like blueberries but have a flavor closer to strawberry! Photo from Creative Commons

The Chilean guava or murta is a fruit somewhat unknown to the American markets. Because of this, not only is its taste unique, but it is known by various names. The history of this plant has been long and complicated and, in a world full of diasporic fruit journeys, it is an honor to write about a plant endemic to my homeland of Chile.

PLANT INFO AND NAMES

Ugni molinacea, the Chilean guava, goes by a variety of names depending on which part of the world you’re in. In its homelands of Chile, its original name given by the native mapuche people is üñi or ugni berry. Throughout the south of Chile, and in some parts of Argentina, it is also referred to in Spanish as murtilla, mutilla, and murta, among other folk names. It was given the name murta by Spaniards which stems from the Spanish word for myrtle. In the early 2000s, an Australian chef traveled to the south of Chile and stole several murta plants. He brought them back to Australia and renamed them Tazziberry or New Zealand Cranberry, suggesting that they were from these regions rather than Chile. After some debate (and perhaps a lawsuit), the name most understood globally today is Chilean guava. For the rest of this article, we will use the Spanish name murta.

Murta is a small shrub in the myrtaceae, myrtle family which means it’s related to other tropical guavas, clove, and eucalyptus. Given the right conditions, murta can grow anywhere between 4-6 feet. Murta shrubs have dark green, waxy leaves with hints of red and their leaves stay on through the winter. The flowers are a beautiful soft pink color with 4-5 petals and its berries are a deep red color when ripe.

Murta in bloom. Photo from Creative Commons

There are a couple of popular varieties of murta that have been commercialized globally in the last decade, the most common being “perla roja” or Red Pearl and “perla del sur” or Pearl of the South. Red Pearl murta have tougher skin and are sweet. Pearl of the South murta have softer skin and are less sweet. It is said that there are around 7 varieties of murta growing in the south of Chile and dozens of varieties of guavas in central and south America.

FRUIT PROFILE & BENEFITS

Please see our disclaimer at the end of the article before consuming this or any other unfamiliar plants.

If I had to compare murta to a common fruiting shrub, it is most similar to a blueberry, with an external colorful skin and white internal fruiting body. The leaves are full of essential oils and the fruit tastes similar to a strawberry. These types of berries receive a lot of praise in the health community because they are high in antioxidants. Antioxidants are compounds that help counteract free radicals in the body, meaning they help cells stay strong as they combat external environmental stressors like air pollution and sun damage. Other native Chilean bush plants, like maqui and calafate, have gained popularity over the past couple of years for similar reasons.

ETHNOBOTANICAL & HISTORICAL USE

Murta has been used for thousands of years by the mapuche people native to the south of Chile. It is said that it has beneficial properties for both internal and external use in the human body. Internally murta has properties that help reduce inflammation and to support the digestive system when taken as a pre or post meal liquor. Externally it is used to help repair and heal wounds to the skin. In recent years, cosmetic brands have adapted murta into their formulas to support cell generation due to its antioxidant and cicatrizing properties. It is said that Charles Darwin came across this plant in his journey to South America and when he shared murta with Queen Victoria it became one of her favorite fruits.

HOW DOES IT GROWS IN CHILE

To understand murta we must understand where it comes from: the lush native forest of the mid to south of Chile. It’s a coastal plant often growing in places near the ocean, lakes or mountain rivers.

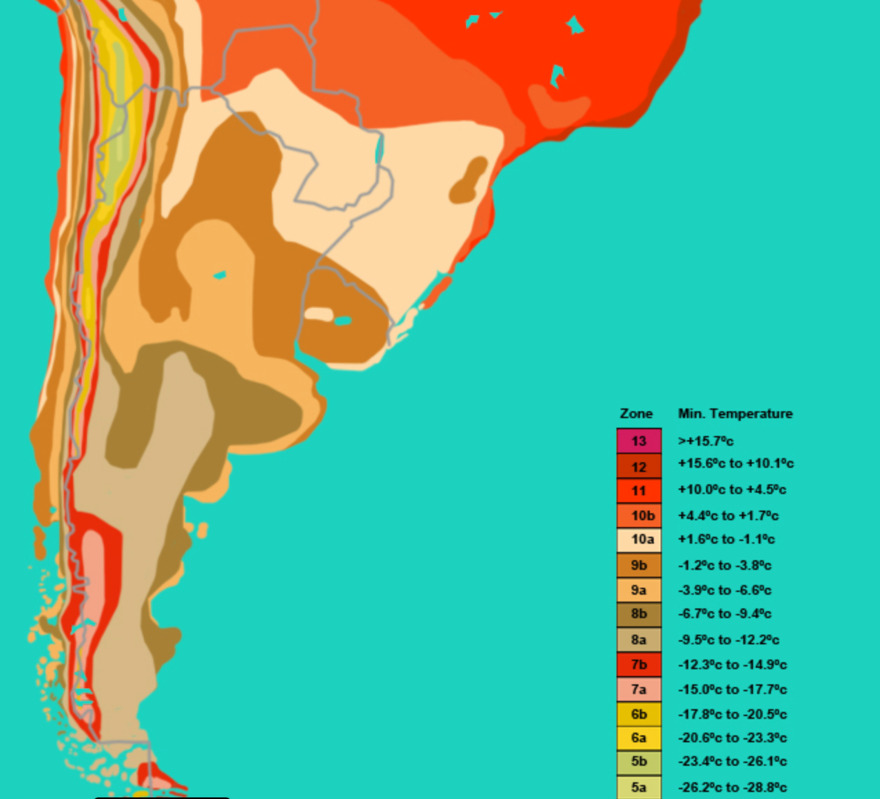

Zone map of Chile, which includes some of the few temperate regions of South America and some plants like murta that may be viable in Philadelphia now or in the near future with climate change. Photo from Davis Landscape Architecture

The area murta grows in ranges from the Maule region (zone 8) until the northern Patagonia (zone 9a). It grows best in a wild forest and tends to be surrounded by medicinal native trees like boldo and arayan which provide some shade. Though it is a cold resistant plant, murta is not completely tolerant to intense, frosty winters. It loves humidity and requires frequent watering, especially when it is young. In the southern hemisphere it is often ready to be harvested around April, which would be akin to late September or early October in the Northern Hemisphere. To increase its yields, it’s best to gently prune the murta shrub once a year in the winter.

PREPARATIONS

Murta is very much the pride of the south of Chile and not commonly used or even known in parts of the north region. Because of this, there is a rich culinary and cultural connection to the plant. It is tradition for some families to go out to forage together in late April early May. In the city of Puerto Varas, there is a whole weekend long festival dedicated to celebrating the plant, filled with pie bake offs and new experimental ways of incorporating the fruit into baking.

Photo from https://turismo.ptovaras.cl/noticias/detalle/fiesta-de-la-murta-2022

The most popular dish at this festival is the Kuchen de Murta, which is a simple tart made with the fruit. There are a variety of ways it is preserved in this region, the most common being Murta con Membrillo, packed together with quince fruit and served as a jelly for toast or baking.

In the Los Lagos region, people make the traditional Murtado, a digestive liquor made with murta berry and aguardiente, a distilled spirit. This drink is served before or after dinner and is said to be sweet and helpful for appetite.

HOW ARE WE GROWING IT AT POP

Orchard Assistant and blog author Carolina Torres planting the murta shrub in the POP Learning Orchard in May 2023 (photo: POP)

When Phil told me we’d be growing murta at the POP Learning Orchard I was so excited and curious about how we would adapt and protect it to the slightly different climate of Philadelphia. Being that this plant usually grows in zones 8-9 and Philadelphia is still technically zone 7b, it will serve as an experiment to see how our less harsh winters and changing climate allow us to grow crops from different climate hardiness zones. As temperatures in Philadelphia shift closer to zone 8, the plant might be able to adapt seamlessly. We have planted one murta plant in the ground in the first row of our orchard near the currants; we may experiment with wrapping this in row cover fabric to provide additional winter protection. Another murta will be planted in our soon to be built high tunnel with other zone 8 plantings. Since we have an orchard filled with ecological biodiversity and layers, I imagine the plant could thrive in an environment that resembles something similar to its native habitat. Stay tuned to how our growing season will go!

MORE INFO:

https://guavabaya.com/blogs/noticias/la-murta-el-oro-verde-de-la-cosmetica

This edition of the POP blog prepared by Carolina Torres, Orchard Assistant.

SUPPORT US! If you found this entry useful, informative, or inspiring, please consider a donation of any size to help POP in planting and supporting community orchards in Philadelphia: phillyorchards.org/donate.

DISCLAIMER

The Philadelphia Orchard Project stresses that you should not consume parts of any wild edible plants, herbs, weeds, trees, or bushes until you have verified with your health professional that they are safe for you. As with any new foods that you wish to try, it is best to introduce them slowly into your diet in small amounts.

The information presented on this website is for informational, reference, and educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as a substitute for diagnosis and treatment by a health care professional. Always consult a health care professional or medical doctor when suffering from any health ailment, disease, illness, or injury, or before attempting any traditional or folk remedies. Keep all plants away from children. As with any natural product, they can be toxic if misused.

To the best of our knowledge, the information contained herein is accurate and we have endeavored to provide sources for any borrowed material. Any testimonials on this web site are based on individual results and do not constitute a warranty of safety or guarantee that you will achieve the same results.

Neither the Philadelphia Orchard Project nor its employees, volunteers, or website contributors may be held liable or responsible for any allergy, illness, or injurious effect that any person or animal may suffer as a result of reliance on the information contained on this website nor as a result of the ingestion or use of any of the plants mentioned herein.