Most of us have seen a stink bug (Halyomorpha halys), whether it’s crawling in your house or on your crops. These mottled grayish-brown bugs are ¾’’ in length, six-legged, and have a triangular or shield-shaped body and are probably most perceptibly known for the nauseating stench they release from their thorax when disturbed or crushed. But, have you ever wondered about the story of these beautiful, pervasive, yet destructive creatures?

One of the most versatile pests found in Pennsylvania, these bugs can overwinter beneath brush, under tree bark, in wood piles, or even in your warm wintertime home. When the weather warms, they migrate outside to breed, feed, and devastate your harvest — all in the same year.

The female lays clusters of 150 eggs on plant leaves, trees branches, or on houses, which can range in color from yellow, brown, white or pink depending on the aging of the nymphs inside. In their nymph stage, the insects are flightless but multiple stages of breeding can happen in the course of the season — meaning their population increases significantly as crops move toward maturity. A field guide to stink-bugs depicting their life cycle, species variety, and feeding habits can be found here.

Brown marmorated stink bugs are the most widespread species and are not native to the region. This invasive East Asian species arrived in Pennsylvania in 1996, likely on shipping crates. Another stink bug species, Harlequin bugs/beetles, are a major pest for cabbage family crops in the region.

Lacking the natural predators needed to control their spread, stink bugs have flourished until their population growth came to the attention of scientists in Allentown a few years later in 1998.

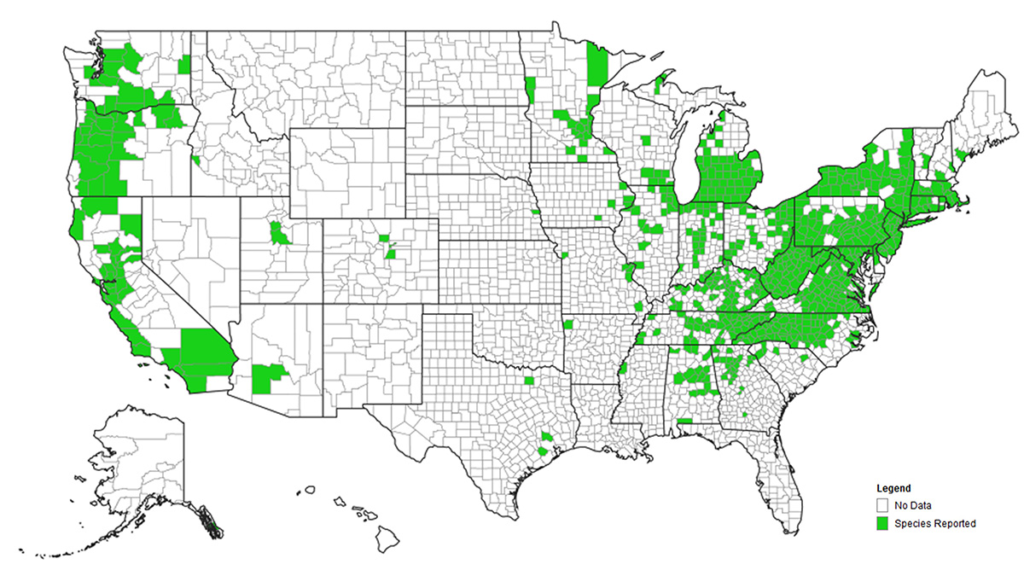

After the first sighting in Pennsylvania, the stink bug made its way to New Jersey by 1999, Maryland by 2003, West Virginia and Delaware by 2004; now the only states that do not have stink bugs are Louisiana, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and Alaska. They are also migrating on a global scale due to their ability to cling to different forms of transportation.

Brown marmorated stink bugs feed on a wide variety of fruiting plants we grow in our orchard spaces including apples, raspberries, stone fruits including peaches and apricots, figs, mulberries, citrus fruits and persimmons. They’re fruit lovers (how can we blame them!) but they will also settle on feeding on fleshy stems and leaves. They also consume other plants often grown in North America such as beans, corn, tomatoes, soybeans and many ornamental plants and weeds. For a full list of high, moderate, and low risk crops, see the StopBMSB website.

Besides seeing the stink bugs themselves, you might also notice signs of their feeding, such as a distortion referred to as “cat facing,” the development of spongy areas, or internal tissue damage, as with the images of these affected apples (below), which can lead to more decay, fallen fruit, and spoilage.

Stink Bug Prevention

There are a number of mechanical, chemical, and biological controls you can use to lessen damage from the stink bug’s piercing-and-sucking mouthparts this season. Keep areas around gardens clear of tall grass, brambles, downed limbs and litter to help minimize spaces for overwintering. By building good soil life and adding regular spring and fall applications of compost to the base of your trees, you can also help to build a vibrant soil ecology to out compete predation from these insects. Row covers, trap crops, pheromone traps, and use of beneficials can also help.

If you have the time and resources, you can grow early crops of stink-bug favorites such as sweet corn, amaranth, and okra which can be destroyed once they’re infested with the pests.

Beneficial insects can also be helpful in controlling stink bug populations. You might consider planting flowers and herbs to help attract parasitic wasps, ladybird beetles, minute pirate bugs, lacewings and other allies that can help control their populations by feeding on stink bugs during stages of their development. The umbel family of plants (fennel, dill, queen anne’s lace, etc) are particularly effective at attracting some of these beneficials, as are other small-flowered plants like yarrow, coneflowers, and asters.

Spray applications of kaolin clay on areas of heavy feeding, or neem oil and insecticidal soap (especially earlier in the season) can help provide barriers to stink bugs’ feeding and mating. In the case of severe infestations, you might also consider applying pyrethrin. Check out the linked POP articles to understand the uses of these organic sprays!

And, if stink bugs have begun to overwinter in your home, Planet Natural recommends the following fix: “Fill an aluminum turkey pan, preferably recycled, with an inch or so of water and stir in a little dish detergent. Shine a lamp (like a desk lamp) on the surface and leave it on overnight. The light attracts the bugs who land in the water and are held by the detergent. From there, you know what to do.”

Resources:

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/03/12/when-twenty-six-thousand-stinkbugs-invade-your-home

https://www.pestworld.org/pest-guide/occasional-invaders/stink-bugs/

https://www.rodalesorganiclife.com/garden/stink-bugs

https://extension.psu.edu/brown-marmorated-stink-bug

EDDMapS. 2017. Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. The University of Georgia – Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Available online; last accessed 30 November 2017.

https://www.rodalesorganiclife.com/garden/stink-bugs-garden

https://www.planetnatural.com/pest-problem-solver/garden-pests/stink-bugs/

This POP Blog post was written by POP 2017/18 Repair the World Fellow Megan Brookens.

SUPPORT US! If you found this entry useful, informative, or inspiring, please consider a donation of any size to help POP in planting and supporting community orchards in Philadelphia: phillyorchards.