Food Forests are not an unfamiliar concept for Philly’s urban agriculture advocates. This model has actually been studied and adapted in the city’s parks, schoolyards, houses of worship, and vacant lots for years.

What is a Food Forest? And why Food Forests?

Many are familiar with the concept of forests, where everything is lush without mowing, weeding, spraying, digging or the use of artificial chemicals. This environment had naturally supported and sheltered humanity. In contrast, imbalanced practices in modern large-scale agriculture have resulted in soil erosion, salinity, destruction of the ecosystem, and the situation is worsened because of the overuse of chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

In the forest, things are abundant and spectacular on their own, because the multiple interdependent horizontal and vertical layers are all active participants, holding and supporting one another. Imagine being under a layer of dense, green canopy: black walnuts, white oaks, and honey locusts with vines winding around. Sunlight tries to penetrate through, shedding spots of light on the ground layers of herbs, mushrooms, and ripe chestnuts that have fallen down to the forest floor. The shrubs are extra leafy and the color of delicious crabapples gives a playful note to the soothing atmosphere. Imagine the excitement of being able to wander through this space and having surprising forage of random healthy fruits, veggies, and herbs. The place I just described is not far away in the forest or an urban fantasy, it is John Hershey’s Nut Tree Nursery in Downingtown, PA, North America’s Oldest Food Forest.

The concept of a food forest has its roots in permaculture, and the collected wisdom of many indigenous traditions, whose philosophy advocates for managing agricultural landscapes in harmony with nature.

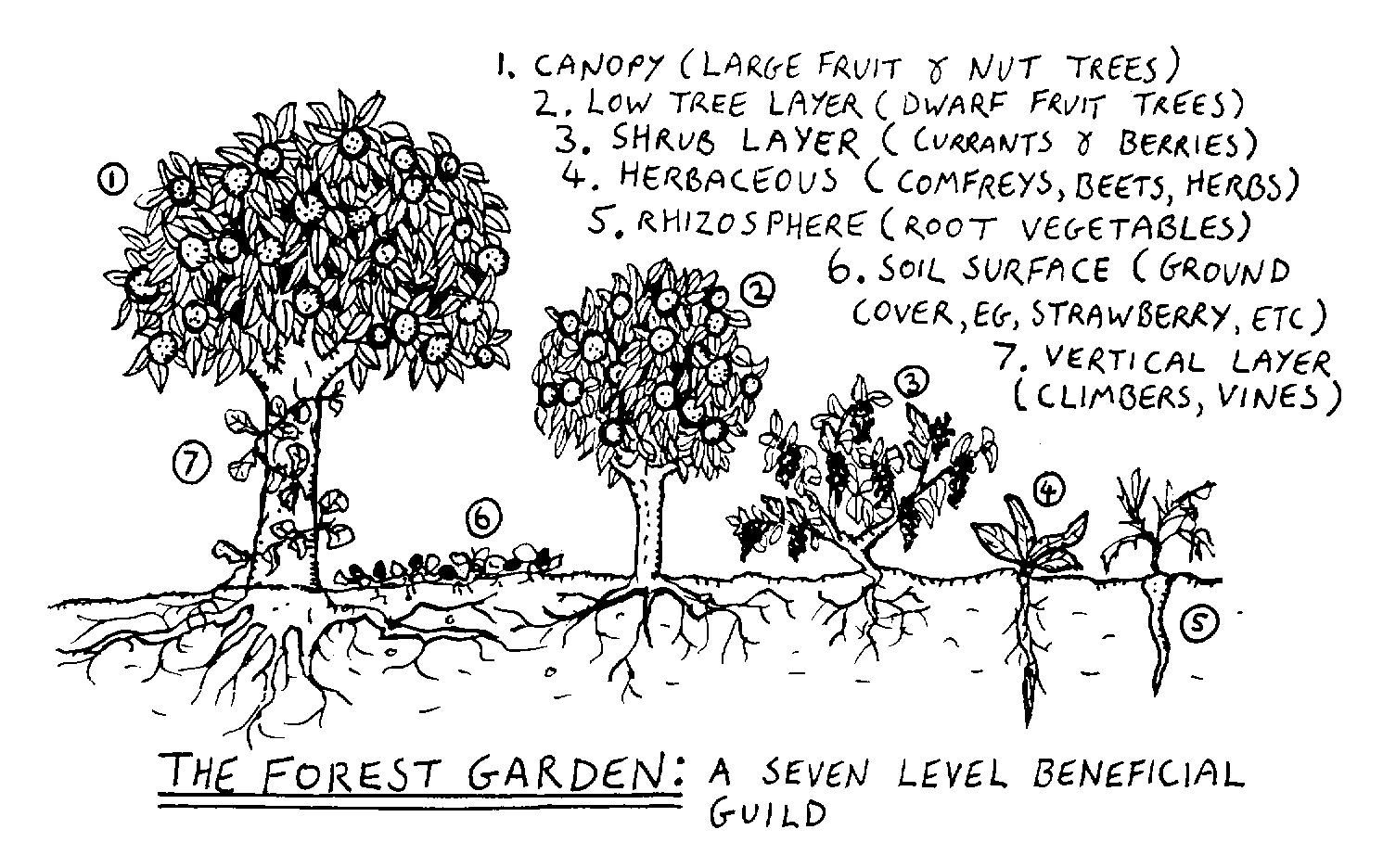

In a food forest, plantings are ecologically designed to mimic how nature grows on multiple layers within a forest, and are chosen carefully (mostly perennial, low-maintenance crops that leverage natural nutrient inputs, drainage patterns, and climate) to produce the food we can eat, to enrich the soil, attract pollinators, and ultimately to enhance sustainable production. Nut and fruit-producing trees and shrubs are planted with herbs, vines, and ground flora, making up the sophisticated layers that produce fruits, vegetables, and edible greens and roots. This is the most sustainable food production system possible; “perfected, refined and cared for by Mother Nature herself”.

What does it mean to have food forests in Philly?

The city now known as Philadelphia was stewarded by members of the Lenni Lenape Nation, a confederation of villages before the arrival of the English settlers. The Lenni Lenape were an agricultural society that had a thriving farming economy: “The crops were tended by the women and were not planted in fields which were fenced”, according to an article from Native American Roots. As Historic Fair Hill notes, their agricultural method involved planting different crops together to create a naturally fertilizing and pest-resistant garden, and foraging for nuts, herbs, and mushrooms. Their balanced, healthy diet was further supplemented by fish caught in the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers, and game hunted in the surrounding forests.

Learning from this wisdom and other permaculture resources, our communities in Philadelphia have been increasingly taking up the practice as a way to combine urban agriculture goals with goals for food and environmental sustainability and justice, community development and regeneration, urban beautification and recreation.

With many of its 40,000-plus vacant lots transformed into community farms, Philadelphia has already been known for its extensive network of community gardens. However, a community garden system is somewhat exclusive in comparison with the food forest system as it requires membership fees and the time to set apart to grow food yourself. Thus, despite the prominent number of community gardens, the city is still home to several food deserts, neighborhoods in which fresh produce is expensive and difficult to access. Taking the issue of food justice into consideration, advocates of community food forests promote local foraging, which means that the system is run by community members, the products are distributed and consumed by everyone, prioritizing those in need, and the possible surplus of a food forest as communal democratic meeting space is enjoyed by everyone. Thus, the rise of community food forests in Philly correlates with positive changes in social and community building consciousness, and dialogue about local food systems and access. For example, many food forest advocates have been providing wonderful resources for those who want to reclaim sovereignty over food production during times of crisis. Additionally, with its healing ability, food forests are magical pills that replenish urban soil and create new wildlife habitats. The opening of some truly public forest gardens will indeed have positive effects on both Philly’s ecosystem and the human food equity and food consumption culture.

With these benefits and the resources the city has to offer, how has the concept been put into practice?

Responding to the city’s demand for food security, the Philadelphia Orchard Project is one pioneering urban agriculture-focused organization since 2007. POP partners with other community groups to plan and plant orchards filled with useful and edible plants in neighborhoods across the city. Using the key elements of Food Forests in its community garden projects while continuously promoting the concept of permaculture, POP helps to educate and build a knowledge-base and culture of sustainable orcharding and fruit-growing. A twist to POP’s adjustment of the idea was that not all of its partner sites are open for public harvesting. However, according to Phil Forsyth, Philadelphia Orchard Project co-executive director, “the food does have to get into the community in one way or another,” such as through food distribution or after school programs. It is critical that “the majority of what’s harvested gets out into the neighborhood for free.”

POP assists with food forest across Philly, each has its own goals and supported community. Awbury Food Forest demonstrates permaculture techniques that can be used in home gardens. The Cobbs Creek Community Environmental Education Center’s small food forest is used in on-site programs such as school and camp visits. The Overbrook School for the Blind food forest provides fruit and educational opportunities for its students, and through this partnership, POP has been involved in the creation of sensory-based lesson plans. Philadelphia Ronald McDonald House’s food forest orchard is part of a new landscape designed to help the families of seriously ill children staying at the facility. Preston’s Paradise food forest expands food production and access in their neighborhood of West Philadelphia. In Orchard Partner Stories 2019, Lee Stough from Overbrook School for the Blind’s shared that “The facial expressions of the students are all different in how they respond to the taste of the berries. The funniest is the sour berries and you get the puckered up reaction. For some of the students, it is the first time that they are exposed to fresh berries.” And Jon Hopkins shared in Orchard Partner Stories 2017, “Our students had an opportunity to make peach cobbler with freshly harvested peaches and many neighborhood residents were regularly harvesting peaches for their families”, at PhillyEarth food forest.

One of the most recent Food Forest projects, the Fair Amount Food Forest, was co-founded by Michael Muehlbauer, the agricultural engineer and orchardist (and former POP orchard director). The concept of a food forest is optimized here: a community-led, publicly-accessible, and educational food forest garden in Fairmount Park created through collective and connective efforts.

According to Michael, FAFF has been explored slowly and intentionally in response to community feedback, organic connections, and willing partners. Through years of community outreach, input, and a community design meeting at Mander Recreation Center, a landscape was designed and further refined through review with Philadelphia Parks and Recreation, which includes a wide variety of common and unusual food-producing, medicinal and ecology-supporting plants and site features desired by community members. As for the time being, they are keeping a nursery of plants; “we hope to sign a lease with the City this year and to begin with planting and community activities as that becomes possible”, said Michael, “things have kind of been on hold during this whole crisis, but we would like to still move forward.”

Food Forests have also influenced the Urban Forestry and Ecosystem Management Division of Philadelphia Parks & Recreation for its pilot project, Agroforestry Edges. In this case, food forests will “enhance and expand edge conditions along forested areas to enhance tree cover along wooded edges that promote woodland function, while supporting productive landscapes (nut or fruit harvest), community engagement and awareness”, said Joan S. Blaustein, former Director of Urban Forestry and Ecosystem Management Division. According to Joan, it took them some time as PPR staff to convince the administration to introduce orchards into the system in the first place as the concept of encouraging park users to harvest fruits was new. The first site to be implemented was at the Horticulture Center in 2013 with support from Penn State Master Gardeners and POP. Because this concept was one of its kind in Philly, the first location worked to attract attention and to educate folks about the way forest gardens are structured. There were also plans to install another forest garden area in East Fairmount Park where there the project would have involved clearing invasives and then replanting with a forest garden. Unfortunately, that project had not moved forward by the time she retired due to other priorities taking precedent in East Park.

Philly’s food forests can be found in a variety of places: churches, universities, vacant land, arboreta, and have been practiced for years. Looking at these initiatives and organizations, it is apparent that each idea and project has its own impacts, each with its own interpretations and adjustments. But the list also points to an undeniable fact that despite challenges, Philly’s food forest advocates are spreading their messages in their own steady, organic, and resilient way to promote a culture of sharing, stewardship, and nature-centered health.

References:

https://www.phillymag.com/news/2018/07/07/downingtown-food-forest-urban-farming/

https://www.phila.gov/media/20171220162100/Parkland-Forest-Management.pdf

http://aquaponicsalive.blogspot.com/2014/10/a-food-forest-in-philadelphia.html

https://www.permaculturenews.org/2011/10/21/why-food-forests/

https://nextcity.org/daily/entry/food-forest-idea-sprouting-roots-in-philadelphia

This POP blog post prepared by POP 2020 Intern Ngoc Pham with the guidance of POP Co-Executive Director Kim Jordan.

SUPPORT US! If you found this entry useful, informative, or inspiring, please consider a donation of any size to help POP in planting and supporting community orchards in Philadelphia: phillyorchards.org/donate.