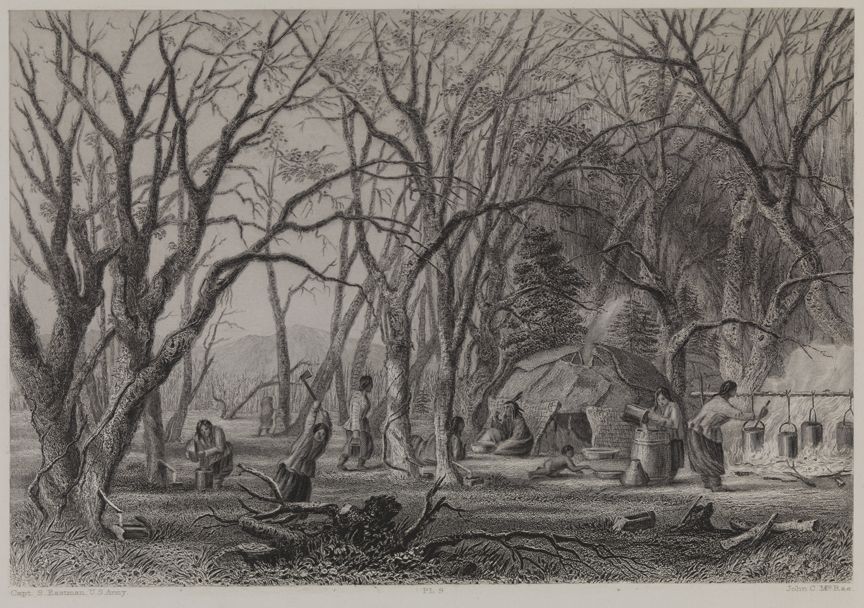

“Indian Sugar Camp” (1853-1856) by John C. McRae after Seth Eastman (Source)

INDIGENOUS ORIGINS

Maple sap is one of the oldest food products in North America. The development of sap into food, medicine and a variety of other products is knowledge cultivated and passed down from the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island. While the exact origins of sap harvest and production into syrup (a process known as sugaring) cannot be traced to a specific tribe, its discovery is surrounded by rich lore. Take for example, the Wabanaki legend of how Glooskap, a cultural hero of the tribe, who saw his people drinking the thick, sweet syrup straight from the tree in excess, while the village declined into ruin. When the people refused to restore the village, he filled all the maple trees with water until the thick syrup was a watered down sap that had to be boiled slowly before becoming syrup again. The sap would only be available for a limited time as a reminder of the error of their ways and to offer gratitude and honor towards the gifts given to them by their Creator.

Indigenous communities harvested sap by cutting a “V” shape into the bark of the tree. Sap would flow out into baskets and be taken to troughs where they would repeatedly freeze the sap and then discard the ice to remove the water from the sap into a more concentrated solution. The sap could then be boiled into syrup and/or maple sugar products. In many tribes such as the Ojibways of the Great Lakes, the Wyandots of the Detroit River, and the Indians at Pidgeon Lake, this labor was a communal practice where women would migrate their families to camps called “sugar bushes” and all hands would be on deck to prepare troughs, collect sap, boil sap and regulate the fire.

Because maple sap is the first harvest of spring, it is known as a time of ceremony, celebration and a symbol of surviving the winter into a new beginning. In her book, “Braiding Sweetgrass”, Robin Wall Kimmerer recalls this time as the Maple Sugar Moon:

“Our people call this time the Maple Sugar Moon, Zizibaskwet Giizis. The month before is known as the Hard Crust on Snow Moon. People living a subsistence lifestyle also know it as the Hunger Moon, when stored food has dwindled and game is scarce. But the maples carried the people through, provided food just when they needed it most. They had to trust that Mother Earth would find a way to feed them even in the depths of winter. But mothers are like that. In return, ceremonies of thanksgiving are held at the start of the sap run.”

THE OAK LANE MODEL WITH JETHRO HEIKO

Between late January and early March, 3 sugar maple and 3 red maple trees were tapped at The Woodlands cemetery in West Philadelphia. Sap was processed at the Oak Lane Maple sugar shack. Pictured above is the POP share for participating in the co-op program where “shareholders” who provide sap are given a portion of syrup at the end of the season (Photo Credit: Left, Courtesy of Jethro Heiko Right, Phil Forsyth)

“Maple season is a great way to celebrate ambiguity because people are like, ‘Well when are you tapping the trees?’ and I’m like, ‘I don’t know… the trees will tell me.’ Not everything happens on a schedule.”

I was on the phone with Jethro Heiko a few days after New Years Day, the ultimate period of ambiguity. Our modern calendars tell us it’s the start of the New Year, some of us even make resolutions for new beginnings, but when you look around, nature is in deep rest. The liminal wintry space after the holidays leaves a long quiet until the first promise of spring.

Jethro and I were attempting to coordinate logistics for maple tapping at the Woodlands Cemetery where the POP Learning Orchard and Headquarters is currently located. We talked in estimations while I scribbled down potential dates and eventually I sighed and laughed to myself the way I often do when I’m on nature’s time.

Jethro wears many hats: community organizer and educator, artist, entrepreneur, father and most recently the Community Engagement Coordinator for Stockton University’s Maple Program and founder of Oak Lane Maple. After tapping the sugar maple tree in the backyard of his North Philadelphia home in East Oak Lane in 2020, Jethro caught the tapping bug. He immediately wanted to connect with others over his newfound passion through curiosity, skill-sharing and community.

“Trees are socially valuable, therefore they should be socially shared,” he said, when he talked about how he started knocking on the doors of neighbors who also had sugar maples on their property. What started as a local neighborhood project has now expanded into a local maple tapping and processing program called Oak Lane Maple with community members who offer their trees to be tapped as “shareholders” who in return, receive a portion of the syrup while another portion is sold to fund the program. Jethro works part-time as the Community Engagement Coordinator for Stockton University, expanding his maple tapping efforts to parts of South Jersey. This year, a grant through Stockton allowed him to acquire an industrial evaporator to further the development of a sugar shack that would be built and funded in partnership with Wyncote Academy. The sugar shack program would be a hands-on way to connect students to maple tapping from collection through processing.

From left to right: Myco and Jacob prep collection buckets, Oak Lane collection bucket hangs on a sugar maple in East Oak Lane, Jethro sets up a collection container (Photo Credit: Sharon Appiah)

POP staff had a training day with Jethro in East Oak Lane in preparation of tapping 3 sugar maples and 3 red maples at The Woodlands. While we learned how to tap trees ourselves, what was more interesting to watch unfold was how Jethro was able to use something as simple as collecting sap as a means of building community. With each stop, we chatted with neighbors, encouraged first-time tappers while they drilled their first holes and learned about how they, too, became maple sap believers. It’s no wonder Philly Mag’s most recent write-up about Jethro suitably named him “Philly’s Maple Syrup Evangelist.”

“Syrup is a story, a connection between trees and the community.” For Jethro, it’s not just about the syrup, it’s about how maple tapping can serve as another tool for connection between us and the people and organisms around us. Once the trees are tapped, sap still needs to be collected every few days and dropped off at the sugar shack for processing. After processing, the sweet syrup is equitably distributed no matter how much sap was offered per tree. In its own way, the Oak Lane model is a modern continuation of the Indigenous communal efforts of sharing the labor and rewards that maple tapping still offers us to this day.

MAPLE TREE IDENTIFICATION

Pictured Left: Dormant sugar maple bud (Photo Credit: Plant Image Library) Pictured Right: Dormant red maple bud (Photo Credit: Gwendolyn Stansbury)

In Pennsylvania, there are six common species of maple trees: sugar maple (Acer saccharum), red maple (Acer rubrum), silver maple (Acer saccharinum), norway maple (Acer platanoides), striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum) and box elder maple (Acer negundo). Of the six, the most commonly tapped maple trees for syrup are the sugar and black maples because of their higher sugar content. Sugar and black maple sap contain about 98% water and 2% sugar. It typically takes about 40 gallons of sap to produce one gallon of syrup. Red maples are also commonly tapped for syrup and despite not being as sweet as the aforementioned maples, they still produce an excellent quality syrup! In addition to maples, other tree species can also be tapped for syrup production, including walnuts, birches, and sycamores.

Collecting sap has a 4-6 week window and is typically collected during late winter into early spring when the day temperatures are around or above 40℉ and night temperatures are below freezing. Trees in Pennsylvania should generally have their first sap flow in mid to late February however, these estimated dates are prone to change and milder winters mean tapping can begin as early as late January to early February (as I personally experienced this year!).

Tapping maple trees for sap first requires proper identification. The bark of the sugar maple tree is grayish-brown with wide vertical ridges, sharp-pointed brown buds, an opposite growth pattern on branches and a long stem on leaves with 5 lobes. Black maples look similar with a few distinctions: the ridges on the bark of black maples are narrower, 3 distinct lobes rather than 5 and if you’re able to ID a black maple while there are still leaves on the tree they have fuzzier underside and mature leaves have a tendency to droop at the edges. Red maple trees also have 3 lobes on their leaves, but the dips in between them have a sharp “V” shape. The buds on red maples are red, rounded and clustered together and mature bark is dark, gray and rough with long scaly vertical ridges.

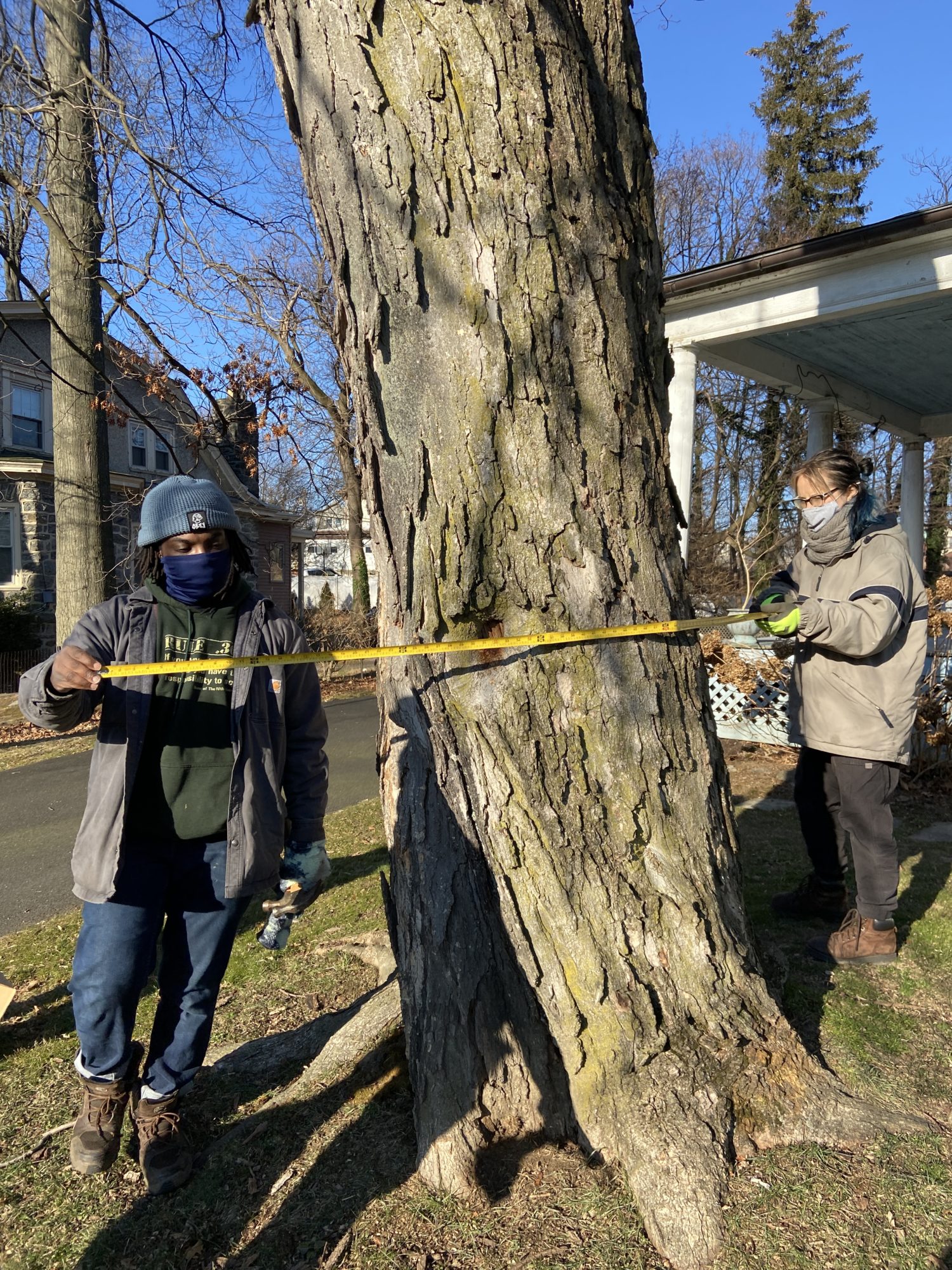

Myco and Simone measure a maple tree to determine how many tap holes to drill (Photo Credit: Sharon Appiah)

After selecting a tree, it must be measured to determine how many tapholes can be drilled for collection. Trees between 10 and 17 inches in diameter should have no more than one tap per tree. A second tap may be added to trees between 18 and 24 inches in diameter. Trees over 25 inches in diameter can sustain three taps. A tree should never have more than 3 taps.

| Diameter in inches | Circumference in inches | Number of taps |

| 10—17 | 31—53 | 1 |

| 18-24 | 57-75 | 2 |

| 25+ | 79 | 3 |

TAPPING TREES

Simone and Phil prepare collection buckets

There are several methods for collecting sap depending on if you’re a curious first-time hobbyist or a professional collecting for large-scale production. If you’re just getting started you’ll need:

- rechargeable drill with a 5/16” or 7/16” diameter drill bit

- hammer

- spile for each tap hole

- bucket with a cover

- sanitized food grade storage containers

- plastic tubing

- nails

Before drilling your tap hole, identify the south-facing side of the tree and if possible, place the taphole above a large root or below a large branch as this is the recommended placement. The height of the tap hole should be wherever allows easy access for collection, but should be at least 3 feet high. If there is a hole in the tree from previous tappings, drill 6 inches from the previous tap hole.

Drill a hole about 2-2½ inches deep at a slightly upward angle to encourage downward flow of sap. A piece of tape can be placed 2-2½ inches from the tip of the drillbit as a helpful guide. Shavings from the hole should be light brown, a sign of healthy wood. Dark brown shavings may be a sign of unhealthy wood. If dark shavings are present, drill a hole in a new location 6 inches away from the previous hole.

Insert the spile into the tap hole and gently *tap* the spile into the new tap hole. Hammering the spile into the tree with force may cause the wood to split.

2 inches from the spile, hammer a nail into the tree. This is where your collection bucket will hang. There are some spiles that may also come with a bucket hook attachment, if preferred.

Drill a hole on one side of your collection bucket about 3-4 inches from the top. Cut about 5 inches of plastic tubing and attach one end to the mouth of the spile and the other into the hole on the side of the collection bucket. Make sure to cover the top of your collection bucket with the lid.

Once collected, sap should either be immediately processed or put in cold storage. Sap left inside collection containers for more than two days may spoil and will need to be discarded.

For more on maple tapping, filtering, evaporating and quality control, check out Penn State Extensions “Maple Syrup Production for Beginners.”

Sources

Indigenous Knowledge and Maple Syrup: A Case Study of the Effects of Colonization in Ontario, Hayley Moody, Wilfrid Laurier University

“The History of Maple Syrup” Maple Valley Syrup

Gluskabe Changes Maple Syrup: An Abenaki Legend

“History” Michigan Maple Syrup Association

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions, 2015

“Maple Syrup Production for the Beginner” PennState Extension

This blog post was prepared by POP Orchard Manager, Sharon Appiah

SUPPORT US! If you found this entry useful, informative, or inspiring, please consider a donation of any size to help POP in planting and supporting community orchards in Philadelphia: phillyorchards.org/donate.