“You HAVE to try the pears I bought from the market yesterday.” My friend and I have a colorful enthusiasm for the things that we love and food is always at the top of the list. Rich Kerrygold butter, the crunchiest Honeycrisp apple, fresh warm millet muffins from Metropolitan Bakery, we delightfully devour simple but decadent foods while raving about the textures, colors and flavors. On this particular day, we were having tea with warm sourdough bread and creamy butter and he set a round, bronze fruit with russet skin sliced in half in front of me on a separate plate. I was hesitant because I’m not a huge fan of pears. I often found many store-bought varieties to be watery, mealy, not very crunchy and a bit dull in flavor. My thought usually was, “Why would I eat this when I can just have an apple?” However, I trusted my friend’s judgment and bit into half of the sliced fruit. I was instantly hooked: as juicy as an apple, if not more, with a delicate crunch and a slightly aromatic pear flavor. It was fibrous, filling, floral and phenomenal… I had experienced my first Asian Pear.

A Brief History

The Asian Pear (Pyrus pyrifolia) is a pear tree species native to China and Japan. The tree has been cultivated in China for over 3,000 years and was most notably planted in large orchards along the Huai and Huang He rivers during the Han Dynasty. The Japanese have been growing and perfecting crunchier varieties of the Asian Pear since the 7th century. Eventually the Asian Pear made its debut to the United States thanks to horticulturalist William Prince of Flushing, NY who imported and planted the “sand pear” variety in 1820. However, we can thank the widespread cultivation of the Asian Pear to Chinese miners and railroad workers who planted the tree along the foothills of the Sierra Nevada during the California Gold Rush between 1848 to 1852 and later Japanese immigrants between the 1840s to 1920s who brought over a large variety of cultivars. To this day, California stands as the largest commercial source of Asian Pears in North America, however the fruit tree can be grown in many other regions in the United States, with the right conditions!

Plant Info

Asian pears are members of the Rosaceae or rose family. While it is in the same family as apples and is sometimes referred to as an “apple pear”, the Asian pear is not a hybrid of an apple and botanically, is a true pear. The aromatic white flowers of Asian pears blossom between late February and mid-April. There are a few exceptions, but Asian pears are not self-fertile trees and produce their best fruit by cross-pollinating with other Asian pear varieties.

Unlike their European counterparts, Asian pears ripen on the tree and are best eaten when firm and crispy. Asian pears have a long list of cultivars but can generally be split into two types: Japanese and Chinese varieties. The Japanese varieties are mostly derived from the aptly named “sand pear” (Pyrus pyrifolia) which refers to the stone cells in the fruit that give the skin its gritty texture. Japanese varieties of Asian pears usually resemble the apple with a round shape and sweet, juicy flesh. When ripe, the fruit will typically have a rusty brown color. Chinese varieties of Asian pears are native to parts of Northern China and Korea and are actually a hybrid of the Ussurian pear (Pyrus ussuriensis) and the Chinese white pear (P. x bretschneideri). These varieties are more cold hardy and with a shape closer to the European pear. The flavor of these varieties have been described as juicy with some tartness and sweetness and their color varies from yellow to brown.

Propagation

Asian pear cultivars are propagated by grafting scions (the young shoot or twig of a plant) to rootstocks (the base and root portion of the plant). Choosing the right rootstock is important because it will determine your variety’s specific plant traits, such as cold hardiness, longevity, fruit yield, size and most importantly resistance to pests and diseases. The two best rootstocks for Asian pears are Pyrus betulifolia and P. calleryana, since both species have roots systems that are resistant to fireblight, tolerant of wet or dry soils, are moderately cold-hardy (-15 degrees Fahrenheit for Pyrus betulifolia and 5 degrees Fahrenheit for P. calleryana). After propagation, Asian pear trees may take three to five years to begin producing fruit.

According to Lee Reich’s “Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden,” Asian pears will grow from seeds that have been pre-treated in order to replicate natural conditions that seeds would experience in the soil over the winter (also known as stratification) but the trees grown from seed will yield fruit that will be different from and possibly inferior to the fruit the seeds originally came from and may take many years to bear fruit.

Cultivation

Asian pears are among POP’s favorite fruit trees for planting and growing in Philadelphia, being delicious, productive, and having relatively less pest and disease challenges than most other common fruits.

Location

Asian pear trees are hardy to USDA zones 5-9 and require around 300-500 chill hours at temperatures lower than 45 degrees fahrenheit each winter. Growing Asian pear trees requires a well-draining soil that has a neutral pH (ideally 6.3 to 6.8). For sunlight, plant in an area that receives at least 8 hours of direct sunlight (for zones 5-7) or partial afternoon shade (for zones 8-9) , since sufficient sunlight activates the initiation of new flower buds for the next season and additional carbohydrate production from the sun may improve flavor development. Keep in mind that Asian pear trees grow large, with at least 15 feet recommended between trees for best airflow and productivity.

Pollination

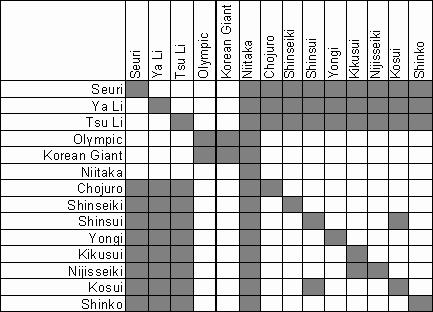

As noted above, cross-pollination between two different cultivars is generally needed for fruit set on Asian pears. However, it is important to keep in mind that not all Asian pear varieties are compatible with each other. For example, bloom time of most Chinese and Japanese cultivars do not coincide and a few specific cultivars are incompatible with each other. There can also be cross-pollination between a late-blooming Asian pear and an early-blooming European pear. For those with only enough space for one tree, some sources list ‘Shinseiki’ and ‘Nijiseiki’ as partially self-fertile. Alternatively, more than one cultivar may be grafted onto the same tree.

For more information on Asian Pear pollination, check out the pollination chart below (courtesy of Hartman’s Nursery):

Watering

Watering is often contingent on humidity, soil type, and the amount of sunlight a tree is getting, but a good rule of thumb is water 1” once a week over the root zone. According to Rain Tree Nursery, “An inch of water is equivalent to about ¾ to one gallon per square foot of soil surface area. The typical three foot diameter planting hole would need 7 ½ to 10 gallons of water per week provided by rainfall or by the gardener.” As with most newly planted trees, watering twice a week for the first month is recommended, and once a week until dormant for the remainder of the year after planting. In Philadelphia’s climate, supplemental water after the first year is generally only needed in periods of extended drought.

Pruning and Thinning

Young Asian pear trees are trained to a central leader form and require annual winter pruning. Remove most vigorous, upright vertical growth. Train primary scaffold branches to more horizontal angles via branch spreaders or other means. Shortening branches with heading cuts may be used to encourage more fruitful growth. Asian pears are prolific producers and need to be thinned throughout the life of the tree to encourage the production of better quality fruit. In late spring, thin all young fruitlets to approximately 5” apart.

You can learn more about pruning on our POP Pruning Guide blog post and thinning on our Thinning Fruit Trees post.

Pests and Disease

POP favors the Asian pear tree as an alternative to planting apple trees since they suffer from significantly less pest and disease issues in our region while delivering a similarly juicy, crunchy and sweet fruit experience. The most concerning disease Asian pear trees are susceptible to is fire blight. Fire blight (Erwinia amylovora) is a bacterial disease affecting pome fruits including apples, pears, Asian pears, and close relatives like quinces and hawthorns. It causes young fruits, shoots, and branch tips to appear blackened and shriveled and is mostly contracted through spring blossoms of fruit trees during wet springs, especially if it is warm and rainy during bloom-time or pre-boom. An infection can be spread from the blossoms and branch tips to the rest of the tree and appears as a black discoloration in the bark. If left untreated, fire blight can continue to spread to major limbs and the trunk and eventually kill the tree entirely.

Treatment for fire blight includes:

> Pruning off 6-12” below the infected site as soon as it is noticed

> Boosting a tree’s immune response using a copper/sulfate spray or biofungicide such as Serenade in early spring

> Prevention by selecting disease resistant varieties such as Shinko, Chojuro, Kosui, Tsu Li

You can learn more about fire blight here.

In recent years, we have also observed some damage on Asian pears from Plum Curculio, which is a common pest insect that, despite its name, attacks most of the common fruits. Read more about managing plum curculio here.

Other pest and disease issues of note are listed in further detail on our POP Pear Scouting Guide

Harvesting

Asian pears are ready to pick as soon as they look ripe on the tree; this may depend on your variety and location, but in Philadelphia this is usually between late August and early September. Ripe Asian pears on russeted cultivars will change from green to light brown or orange and from green to greenish-yellow on smoother skinned varieties. You can always try a sample before harvesting them to make sure! At room temperature, Asian pears will keep for 1-2 weeks and about 3 months in cold refrigeration.

Recipes

Asian pears are a great source of fiber, Vitamin C, K and potassium! They’re primarily consumed as a fresh fruit and are quite delicious, picked and eaten right off the tree. In addition to ciders, sauces, pies, and other desserts, Asian pears are also notably used as a marinade in bulgogi (korean grilled beef) to tenderize the meat and add sweetness. Maangchi has a highly rated bulgogi recipe you can try for yourself!

Ingredients:

- 1 pound of beef tenderloin, sliced thinly into pieces ½ inch x 2 inches and ⅛ inch thick

- For vegetarian option : 10-12 large dried shiitake mushrooms

- ½ cup of crushed asian pear

- ¼ cup onion purée

- 4 cloves of minced garlic

- 1 teaspoon minced ginger

- 1 chopped green onion

- 2 tbs soy sauce

- 2 tbs brown sugar (or 1 tbs of brown sugar and 1½ tbs rice syrup)

- a pinch of ground black pepper

- 1 tbs toasted toasted sesame oil

several thin slices of carrot

Directions:

- Mix all the marinade ingredients in a bowl.

- Add the sliced beef and mix well.

- You can grill, pan-fry, or BBQ right after marinating, but it’s best to keep it in the fridge and let it marinate for at least 30 minutes, or overnight for a tougher cut of beef.

For Vegetarians:

- Use the same marinade above and replace beef with mushrooms. You’ll need 10-12 large dried shiitake mushrooms. Add a few white mushrooms if you like them.

- Soak the dried shiitake mushrooms in warm water for several hours until they’re soft.

- Squeeze out any excess water and slice each mushroom thinly.

- Slice some white mushrooms, carrot, and onion.

- Mix all of it together in the marinade.

- Grill, pan-fry, or BBQ.

For a sweet treat, try an Asian pear crisp!

Asian Pear Crisp by Molly Watson

- 6 Asian pears

- 1 tablespoon apple cider vinegar

- 3/4 cup brown sugar, divided

- 1/4 teaspoon garam masala

- 1/4 teaspoon ground cardamom

- 1/4 teaspoon ground ginger

- 1/8 teaspoon ground cloves

- 1/8 teaspoon fine sea salt

- 1/2 cup all-purpose flour

- 1/2 cup whole wheat pastry flour

- 6 tablespoons (3 ounces) unsalted butter, cut into small pieces

Directions:

- Preheat oven to 375 F. Quarter, core, peel, and chop pears.

- Put pears in a large bowl and toss with vinegar. Add 1/4 cup brown sugar, spices, and salt and toss to combine thoroughly.

- Dump pears into a 2-quart baking dish and set aside.

- In a medium bowl, combine flours, and remaining 1/2 cup brown sugar. Add butter and cut or work the butter into the flour mixture (this can be done with your fingers, a pastry cutter, or fork). Note that you can pulse this mixture a few times in a food processor to great effect.

- Spread flour mixture over pear mixture.

- Bake until center fruit mixture is bubbling and the top is browned and yummy looking, about 40 minutes. Let sit at least 10 minutes before serving. Serve warm.

SOURCES

Lee Reich, Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden

Pears, Washing State University Extension

How To Plant and Grow Asian Pear Trees, Gardener’s Path

Growing Asian Pears, Raintree Nursery

Choosing Pear Rootstock for the Pacific Northwest, Oregon State Extension

DISCLAIMER

The information presented on this website is for informational, reference, and educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as a substitute for diagnosis and treatment by a health care professional. Always consult a healthcare professional or medical doctor when suffering from any health ailment, disease, illness, or injury, or before attempting any traditional or folk remedies. Keep all plants away from children. As with any natural product, they can be toxic if misused.

The Philadelphia Orchard Project stresses that you should not consume parts of any wild edible plants, herbs, weeds, trees, or bushes until you have verified with your health professional that they are safe for you. As with any new foods that you wish to try, it is best to introduce them slowly into your diet in small amounts.

This POP Blog was written by Orchard Manager Sharon Appiah

SUPPORT US! If you found this entry useful, informative, or inspiring, please consider a donation of any size to help POP in planting and supporting community orchards in Philadelphia: phillyorchards.org/donate